- Home

- Michael White

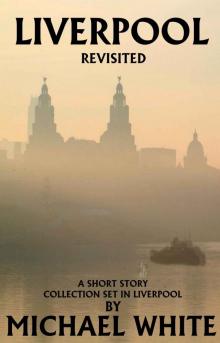

Liverpool Revisited Page 13

Liverpool Revisited Read online

Page 13

“He died in his sleep about three weeks later.” said Sue. “Paul lives in the house now. He inherited it. That and everything else. We go out there to visit from time to time. Have a drink or two in the back garden. He’s very sad most of the time, of course, but we give him what comfort we can.”

“Ah.” said Sarah, moving away from there to where her car was parked. “That’s really sad. Still. Enjoy your six thousand pounds!” she said, and the couple watched her as she got into her car and then waved as she drove away.

“Lovely girl.” said Sue.

“Yeah. But too nice to be a journalist.” sighed Billy.

***

The couple sat on the patio enjoying a drink as the sun began to dip towards the horizon. Sue was doing a crossword, and Billy was just sitting taking in the sun.

“Everything will need a water tonight.” he said, and Sue agreed that indeed it would.

“I can’t help but feel guilty about what we told Sarah.” she said eventually, and Billy just snorted.

“She’s a lovely girl Sue, but she is a journalist. She wouldn’t have been able to help herself!” Sue seemed to consider this for some time. Although she knew that he was right, she still couldn’t help but feel guilty.

“I know it was a very rare coin, but you shouldn’t have told her it was worth six thousand pounds!” she said, nervously.

“It was a very rare coin for sure.” said Billy. “But she is a journalist, and I suppose you’re right. I shouldn’t have told her it was worth anything.” he laughed out loud, and then stopped as if thinking about what he had told her. “I think I could have told her any figure to be honest. She’d have been happy to think it was worth six million pounds if I told her that was what it fetched at auction. But I wouldn’t do that now, would I?” he finished, taking a long swig of his drink.

“Not even if it was true.” And he winked.

The Last Bomb, Aloise's Café and

Death by Cow.

The last bomb that fell on Liverpool in the Second World War fell on the evening of the tenth of January nineteen forty-two in amongst other places, Upper Stanhope Street, Toxteth. I know this for I was there at the time, and remember it well.

You would have thought we had grown used to the seemingly endless series of bombings by then, but I think that we never really had. Of course, we did not know at that time that it was the last bombing raid. As far as we knew it would carry on forever. We were not to know, but that was the last night and that was more than enough. I left the air raid shelter as the all clear was sounded and found myself in hell. Whole streets were now reduced to mounds of burning rubble. I could not reconcile my position in the sense that what I now saw did not match with what I had briefly glimpsed as I had hurriedly entered the shelter hours before when the sirens had begun to sound. The skyline was in flames. Smoke floated in eerie clouds across wide open spaces that hours ago had been houses, businesses. They were now just piles of concrete, metal and glass shattered across the ground. Flames roared across the heavens as an inferno lit the night.

I reached down and helped the Irish lady, who I now knew as Brigid, out from the Anderson shelter, which had presumably been sited in somebody’s garden at some point; for it was only there that you would find an Anderson. Now however, it was simply surrounded by rubble.

“Thank you.” said Brigid in her light Dublin accent as I gave her a hand back up to the surface. We had spent the last three hours alone in the shelter. I did not know her and she did not know me. Yet somehow over that time we had forged some kind of bond as we sat in that buried corrugated iron hut waiting to be blown to smithereens. We had both been lucky to find the shelter when the air raid sirens had sounded, as we were both off course on our journey across Liverpool, if not lost. It was difficult you see, to gauge where you were by landmarks when they continued to disappear every night. The city seemed as if it was in flux and flow, and most of it seemed to be falling down.

“Was this part of Upper Stanhope Street?” she asked, and I looked about me. Though it was night the fires from all around made it quite easy to see, if not to navigate.

“I think it was.” I said. “The lower half, anyway. It’s hard to say. I think there used to be a crossroads there.” She followed the direction I was pointing in.

“That building there.” she said, pointing to what was not a building any longer but a burning pile of rubble. “That was standing when we entered the shelter, wasn’t it?” I nodded and she span on the spot as if trying to get her bearings. Suddenly she hitched up her coat that was wrapped tightly about her as some kind of defence against the cold, and marched towards the pile of rubble which had been hours before the building she had mentioned.

I ran after her. “Brigid!” I yelled. “Don’t go near. The bloody thing’s still on fire. It could collapse or there might be an unexploded bomb in there or something! Come away!” I grabbed hold of her arm to stop her, thinking that perhaps the time spent in the air raid shelter had driven her mad or something. She shook off my grasp but only moved forward a few more feet and then leaned forward to the pile of rubble. To my surprise she spat on the building before almost screaming,

“That’s for you, Alois Schicklgruber, you bastard!” Satisfied with this outburst she returned back towards the shelter and therefore relative safety. I followed her. “Got a smoke?” she asked, and I had to admit that I hadn’t.

“Pretty hard to get hold of these days.” I said, and she agreed. There was an awkward silence. To be honest I didn’t really want to leave her on her own in the middle of a bomb site, but as well as that I was also a little bit curious about what she had just done. So I decided to ask.

“What was all that about, then?” I said. She looked at me as if what she had just done had not been out of the ordinary at all.

“What?” she said, and I seriously do think that she had not got a clue what I was on about. So I asked her again.

“Spitting on that building. Skittle grubber or something.” She laughed out loud at this. I have often thought that only the Irish can laugh the way she did then. It was joy. But it was pain as well, if you see what I mean.

“Schicklgruber.” she said. “He was my husband and father of my child too. Well, that he was before he decided to bugger off abroad from where he came, anyway. Left me up to my eyes in debt, no money and a little one needing to be fed. Just upped and went, the lying bastard. Lower than a snake’s belly, he was.”

Such stories were not unusual for the times. Even before the war money was tight, and there are never any times I imagine when there isn’t a cheating bugger about waiting to take advantage of a woman and then sodding off when it all gets a bit too much for him. We stood in the semi darkness, smoke drifting about us. I wasn’t about to tell her that, however. I wasn’t that soft!

I tried to change the subject as there didn’t seem to be any consolation I could offer her. I waved my hands about me, almost bewildered by the scenes of destruction all about us. “Sorry to hear that. I think the bloody world’s gone mad. Look at all this. No sign of it stopping either. When things get too much I like to think of better times. Friends and love and laughter.”

“Aye.” she said angrily, “And a bunch of daffodils is just about to spring out of my arse! You’re just a young one, you are. Where do you get these daft ideas from?” she finished with a snort.

“You must have had better times.” I said. Times you can look back fondly on.” I remembered something she had said. “What about the birth of your son?” She smiled at that. “There you go. That’s brought a smile back to your face, hasn’t it?”

“Ah, you’re a sly one, at that.” she said, continuing to smile at me, or at the return of a memory. “Walk with me to the church if you don’t mind. It’s only a small way and I could do with some company.” As I was heading that way I agreed and off we strolled, picking our way across the debris, avoiding the fires and rubble scattered all about us. “You’re right.” she said. “There are

many happy memories. Alois - that’s my husband’s name, was from overseas when I met him in Dublin.” She giggled out loud. She sounded like a little girl though I figured her to be in her late forties or so. “We eloped!” she giggled and held her hand to her face, still laughing. “He was a handsome sod, I’ll give him that. I think he had probably kissed the bloody blarney stone too. Charmed my skirts right off me, he did!”

I was glad that the darkness concealed the fact that I was probably now blushing like mad. She was entertaining though! As well as that she seemed to have forgotten all of whatever had been troubling her.

“Anyway. Off to London we went. Then from there to here. Liverpool is a fine city. Little Ireland, I used to call it, and I’m sure that I’m right about that. We set up a cafe’ in Dale Street. Nothing fancy. But it was ours.” She seemed far away now, silent in the dark as we continued to pick our way back to the church. If it was still there, that was. “Later on we had a boarding house in Parliament Street. That was when the money started to go wrong.” She sighed out loud. “Not much longer after that he was gone. Never seen sight or sound of him from that day to this. Back abroad, probably.”

“Sounds like a right bastard.” I said.

“Oh you don’t know the half of it!” she said. “But at first, when we had that little cafe’, they were the best times. Especially when little Patrick came along. That’s when Aloise’s relative came to stay. I had just given birth and Alois sent a telegram to this half-brother of his. He wanted him to be Patrick’s godfather. Family ties, and all that. Foreigners are a bit like that, aren’t they?”

“Not just foreigners.” I said, and she laughed brightly beside me.

“True enough.” she smiled. “I’ll give you that one. Anyway, before long his half-brother arrived from abroad at the pier head, all hugs and kisses. Didn’t have much of a family resemblance, if truth be told. Well. Perhaps just a little. Couldn’t speak a bloody word of English either. Him and Alois were yattering on in foreign and there’s me, just stood there trying to make sense of it all. During the six months he stayed here we communicated entirely through hand signals. Oh, and shouting. Funny little bugger. Mind you, he couldn’t half paint.”

“Paint?” I asked and she made a brushing gesture with her arms.

“Not decorating, you soft lad, you! Paintings of people and trees and what have you. He was really good. Sold a few from the cafe’, we did. He even signed them, like a proper artist and all. “She drifted away into silence once more. “Yes. They were the good times. Al had a thing about ice skating too. Used to go out to the park during the winter he was here. See if the lake had frozen over. If it was he was off onto it, skating like some kind of dancer across the ice. It was something to watch, I’ll tell you.”

“I’m getting confused.” I said. “Al? Do you mean your husband?” She laughed.

“No. Alois was my husband. His half-brother had a foreign kind of name so I just called him Al. Even Alois started to do it after a while. Al himself didn’t even seem to notice, what with his painting and the skating. Always head in the clouds, was that one!” We continued on our way. In the distance I thought I could make out the outline of a church. This must be where Brigid was heading.

“So the cafe’ continued to do well?” I asked, trying to goad her into continuing her story.

“It managed well enough.” she said. “Al helped out with the dishes though he was useless at ordering or waiting or the like. No English, you see? Patrick was christened and life carried on. We even took on a few staff at one point. Wee Mary used to help out with the cooking even though it wasn’t anything fancy. Alois used to get quite flustered if we got busy.”

“Foreign temperament?” I asked.

“Nah. Just a chippy little gobshite.” she laughed. “That house I spat on. It’s where we used to live.”

“Ah.” I said. “I see. “Did you make a special journey just to do that?” She giggled to herself, as if shocked to admit that this was in fact actually the case.

“I did.” she said. “I’m leaving soon.” she paused then, and I considered it rude to pry.

“Now where were we? Ah yes. Poor wee Mary. Used to do such a lovely bacon roll, and that’s a fact. Killed by a wooden cow she was. Terrible thing to happen to a young girl.”

“I’m sorry?” I said, not quite sure I had heard her right.

“Killed by a wooden cow. Fell right on top of her from the Hartley’s factory roof. Stone cold dead she was.”

“A wooden cow?” I repeated, unsure if she was spinning me a tale or not.

“The Hartley’s factory roof?” she asked and I shook my head. “Oh you’re a strange one, for sure! Do you never read a newspaper or listen to the wireless?” she laughed, and I considered telling her that she had got it wrong. After all, it was me that was making sense. She definitely wasn’t!

“The Hartley’s factory is right next door to the railway line and the German bombers would obviously think that a factory right next to a railway line is a good place to drop a bomb or two, I should think.” I nodded. Couldn’t see anything wrong with that line of thought. “So they painted the roof of the factory green so it looks like a field from the air. Seems to be working too. Last time I looked the place was still standing.”

“Where does the wooden cow come in?” I asked.

“Well now. They wanted to make it look just a little more real. Authentic field, if you like. So they got some cows made out of wood and painted them and put them on the roof. One of the night watchmen’s jobs was to move the wooden cows around after dark so they weren’t in the same place all of the time. Only problem is, the wind kept blowing them off the roof.”

“Right onto poor Mary.” I concluded.

“Right onto poor wee Mary. Horrible way to go. Death by cow.” I stifled the urge to giggle. To this day I have no idea whether she was telling the truth or not. But she wasn’t laughing. So I didn’t either. We carried on in the dark, being careful to avoid any potholes or piles of rubble.

“So we were one person down but we coped somehow. We had to. Just got on with it. After six months Al left and returned back abroad, leaving just his skating boots and a pile of pictures behind him. Shortly after that Alois and I set up the guest house. You know the rest.”

We were at the church now. Flames from a half destroyed row of shops lit its entrance. I could see a small group of people gathered in the pool of light and as I watched a young man detached himself from them and waved at Brigid almost as if in relief.

“That’s Patrick.” said Brigid. “He will have been beside himself wondering where I disappeared to.” She turned to face me, her profile lit from the burning buildings nearby. She looked a little serious now.

“Thank you for escorting me back to here.” she said. “It was a daft old thing to do what I did. I know that now. But it was important to me. Thank you.” and with that she reached up and placed a small kiss on my cheek. “Take care.” she said. “And thank you for reminding me of the good times.” She moved away and I too turned to go, at which point a thought came in to my head.

“Brigid!” I shouted and she turned, eyebrow raised. “You could always try and find him by getting in touch with his brother. What was his name again? Schringler or something?” At this Brigid just laughed.

“Schicklgruber.” she reminded me.

“That’s the one.” I said. “If you could find him you may be able to trace your husband through him.”

“Oh, that part of my life is over now. I’ve moved on.” she said sadly. “Besides, Al was his half-brother. They didn’t share the same surname at all. Remember, even Al wasn’t his real first name. It was just what I called him. Besides, I think he may be just a little bit busy at the moment. Hopefully even busier soon.”

“Oh.” I said, beginning to realise that when Aloise had moved out on her, he really had gone for good. He would be almost impossible to trace even if she did want to find him.

“So what was A

l’s full name, then?” “I said. I was young, so very young and probably trying to impress her. “If I ever come to hear of him I could send you a letter telling you. Find Al and you might just be able to find your husband as well.” She smiled and turned to go.

“That’s not very likely.” she said, and moved towards her son who was waiting for her, probably wondering what on earth was going on.

“So what was Al’s real name then?” I shouted over to her weakly, not really wanting her to go. She half turned towards me, a smile upon her face.

“You may have heard of him.” she said, smiling sweetly and turning to go, “His name is Adolf Hitler.”

The Order of Pan

There are secrets within secrets, paths hidden, most for good reason. The order of Pan knows this, and we watch and we wait and listen. Look for the signs. We are good at that. Very good. There are seven of us, one of us to watch over each, and that has always been our number. Guardians we are, and we watch, and wait, and on one night of the year we defend what must be upheld across the world, for if we do not then great evil shall fall upon this earth, and all that we have made will be unmade.

I pulled my cloak tightly about myself and tipped the brim of my hat forwards as some form of defence against the rain. I made way through the darkness and entered what was in light a place for children and sun and play. Now it was the realm of nightmares, and on this night, especially so. In these times there is but one fence to scale, though that has not always been the case. The park entrance now however is open, and I simply cross into it as a shadow. None will see my passing, for they do not know how. In shade and darkness I make my way to where I will be needed as I am needed on this night every year.

I make my way to the statue of the Pan and scaling the only remaining fence there begin my wait. Still the rain continues to pour but I feel neither the cold nor the dampness that surely finds its way into the folds of my cloak, for on this night when I become real to this place once again, I am mortal, yet I remember none of my corporeal existence. I am the guardian of Pan, and that is all. My worries and fears are no longer part of me, for I am formidable and exist only to serve. This ritual is all that I am, and yet it makes me more than a man, more than a shade. I am the guardian of this one of seven, and that is where I begin and end.

Paul McCartney's Coat

Paul McCartney's Coat The Cat Is Back!

The Cat Is Back! Laughs, Corpses... and a Little Romance

Laughs, Corpses... and a Little Romance The Waiting Room

The Waiting Room Into the Light- Lost in Translation

Into the Light- Lost in Translation Six of the Best

Six of the Best Scrapbook

Scrapbook Bob the Balloon, Al Capone and the Two Bob Bouncer

Bob the Balloon, Al Capone and the Two Bob Bouncer The King of the Cogs

The King of the Cogs A Bad Case of Sigbins

A Bad Case of Sigbins To the Lighthouse

To the Lighthouse Overboard!

Overboard! A Challenging Game of Crumble

A Challenging Game of Crumble Conversations With Isaac Newton

Conversations With Isaac Newton The Complete Adventures of Victoria Neaves & Romney

The Complete Adventures of Victoria Neaves & Romney Liverpool Revisited

Liverpool Revisited Dad Comes to Visit

Dad Comes to Visit Lachmi Bai, Rani of Jhansi: The Jeanne D'Arc of India

Lachmi Bai, Rani of Jhansi: The Jeanne D'Arc of India Barf the Barbarian in Red Nail (The Chronicles of Barf the Barbarian Book 2)

Barf the Barbarian in Red Nail (The Chronicles of Barf the Barbarian Book 2) Equinox

Equinox Barf the Barbarian in The Tower of the Anas Platyrhynchos (The Chronicles of Barf the Barbarian Book 1)

Barf the Barbarian in The Tower of the Anas Platyrhynchos (The Chronicles of Barf the Barbarian Book 1) The Medici secret

The Medici secret Jack Pendragon - 02 - Borgia Ring

Jack Pendragon - 02 - Borgia Ring The Art of Murder jp-3

The Art of Murder jp-3 Travels in Vermeer

Travels in Vermeer